by Nicole Yurcaba

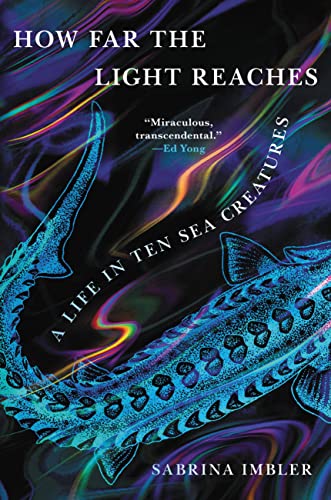

The sea seems to be a common theme and place in many of the books I’m reviewing this summer. I’m taking this as a hint from the universe that I need to return to one of the places where I spend a great deal of time staring into the waves, contemplating my futility–any beach where I can sink my combat boots into the sand. My obsession with the sea and what lies beneath its waves stems back to my childhood–the exact period when my questioning about my gender identity began.Therefore, imagine my elation when I discovered Sabrina Imbler’s How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures via another bookstagrammer’s Instagram post.

How Far the Light Reaches isn’t another boring series of science-laden essays where dogmatic, field-specific vocabulary thwarts common readers from entering its pages. Instead, Imbler’s honest, vulnerable, and conversational writing invites readers into Imbler’s world–one filled with a devotion to sea creatures, a passion for writing, and an embrace of their own queerness. Initially, Imbler introduces readers to the feral goldfish–those which have been cast into ponds, creeks, and streams and grown to enormous sizes. Their hardiness and ability to survive harsh environments in which other fish and creatures quickly perish mirrors the queer community’s ability to adapt and overcome adverse and threatening environments. For example, Imbler poses, “They have confronted seemingly impossible waters, and they have survived.” The goldfish’s confrontation parallels the ever-increasing hotbed of political policies which threaten LGBTQ, and specifically gender-affirming care, rights. Imbler continues, “Maybe there is something universal about wanting to get out. I wonder if the goldfish have any sense of the ocean that lies ahead of them.” Imbler’s contemplation brings forth other imperative questions asked by many in the queer community–”Where do we go? Where do we belong?”

Tangentially, Imbler’s book is about learning to survive in environments which threaten to deny an individual their right to exist. In the same essay about the goldfish, Imbler poses, “What does it mean to survive in the wild. You can’t do it without going wild yourself. We are all capable of reverting to a wilder state.” For the goldfish, the wild “promises abundance” because “Nothing fully lives in a bowl; it only learns to survive it.” The goldfish’s experience becomes synonymous with the experiences of LGBTQ people everywhere, but especially in states like Alabama, which according to a 2020 USA Today article, ranked as the United States’ worst states in regards to LGBTQ rights.

In other essays, How Far the Light Reaches acts as a call to action against climate change. Currently, as global temperatures increase, sea levels rise. So does acidification. Ocean species which never interacted or encountered one another are now coexisting together. One of the most poignant moments of reflection about the dangers of climate change occurs in the essay “My Grandmother and the Sturgeon.” Again, Imbler draws on the theme of survival to ground this essay, as it documents her grandmother’s survival story in a violent, torn, and starving China and reflects on the dwindling number of Chinese sturgeon. The sturgeon have a magnificent heritage. Imbler notes that because of humanity’s unwillingness to acknowledge its role in climate change, “If we translate two hundred million years into a twenty-four-hour clock, we have taken less than one-tenth of a second in the last minute of the last hour to imperil every single subspecies of sturgeon on the planet.” According to Imbler, “Sometime in the next twenty years, scientists predict, the Chinese sturgeon will go extinct in the wild.” The scenes and statistics Imbler poses are dire, even hopeless. However, hopelessness is not the flavor of How Far the Light Reaches, no matter how dire the violence or statistics permeating Imbler’s essays.

Readers only have to look at essays like “Pure Life” to discover that, yes, there are inclusive places where individuals can flourish, thrive, and develop into the beautiful ones they want to become. In this essay, Imbler adeptly captures their own experience of finding a monthly party called Night Crush, a party “thrown by queer people of color for people of color.” Imbler shares their own story of dancing for entire nights in a safe, inclusive space and parallels it with the necessity of hydrothermal vents in the sea, where on their fringes, a variety of creatures–including the yeti crab–rely on the vents for survival. The environment in which the yeti crab thrives is inhospitable to the vast majority of sea creatures, yet the yeti crab–along with tube worms and small mussels, remain resilient. Imbler asserts, “But life always finds a place to begin anew, and communities in need will find one another and invent new ways to glitter, together, in the dark.” As Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill becomes law, and as the largest LGBTQ+ watchgroup issues a travel advisory for Florida because of the law, readers can draw inspiration from and find hope in Imbler’s words.

How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures shares messages of hope, regrowth, and renewal. Thus, it is only appropriate that deep within its final essay, readers find a question that they will return to long after leaving the book’s pages: “How shall you regrow, and in how many ways?” It is difficult to leave Imbler’s book without a renewed sense of self-awareness, self-worth, and self-acceptance, and for Pride Month, this collection of essays is the perfect read.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post