by Stan Galloway

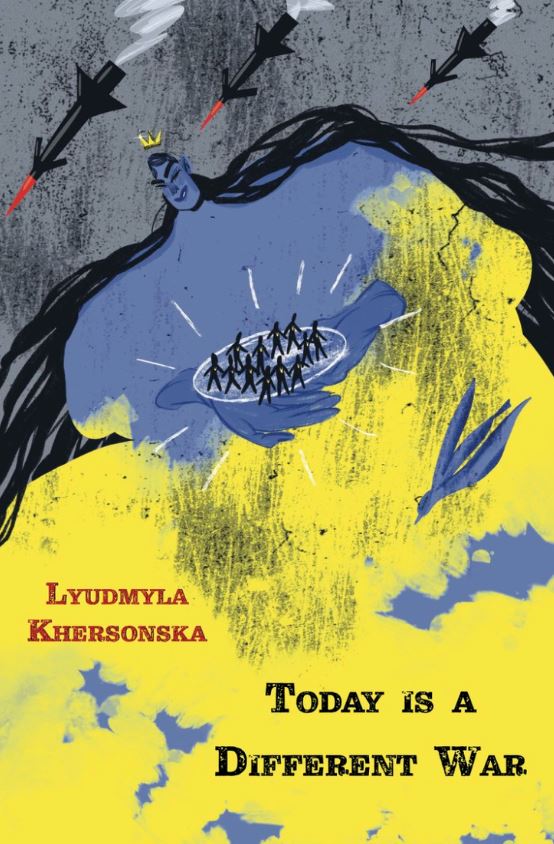

Today Is a Different War (Arrowsmith, 2023) reminds readers that the world is an unsettled and unsettling place. Lyudmyla Khersonska cherishes the living world and, holding its pieces, finds frustration and beauty. Khersonska’s short collection (44 pages) has the rainbow shimmer of house rubble after a storm, “a hurricane or a Grad rocket raining down” (“So This Is It”), its sadness and potential transcending its socio-political context.

Grounded in Odesa, Ukraine, the collection, despite wartime conditions, is literally quotidian: the opening poem begins “In the morning” (War. Day 1”) and the final line of the last poem concludes, “the night is dark, like the day” (“So This Is It”). Echoes of William Wordsworth might be heard in many of the poems. Or those echoes might just as rightly be of Wilfred Owen. In the “today” of this collection, instead of planting gardens, “the war season has started” (“War. Day 6”). “It’s spring out there, / yet a cloud of sulfur gas is rising” (“War. Day 9”). Here readers might recollect that gas in “Dulce et Decorum Est,” Owens’s most famous war poem.

Khersonska mixes that wartime horror of The Great War with the matter-of-factness of having to go on living. “War – it’s inconvenient for a walk, a salad, an outfit” (“How Nice to Take a Walk in the Warless World”). This year’s gardens are “being bombed by a balding, vulnerable / garden gnome” (What’s New? The Gawking”). And inside, “porcelain dinner plates with pale blue flowers” are “broken up by life”; those “flowers never withered” – they were “only slightly effaced” (“I Loved Them So Much”). The fragility of daily life is emphasized, and the effacement of the dishes is amplified in the war’s attempts to efface the nation. Later that year (“War. Day 105), “in Berlin it’s summer, in Ukraine it’s wartime.” This distinction comes about because in “the fourth month of constant shelling,” “The world got used to it” (“The Fourth Month of Constant Shelling”). But, there is no getting “used to it,” for those who watch the skies and feel the ground shake in daily attacks.

Instead of birds, “rockets [sing] outside the window” (War. Day 1). The “silenced birds” are “strategic” targets, along with

shell-shocked cows

“The Ruscists are Firing”

wounded dogs

deafened cats

dolphins cast out onto the beach”

The cat has learned to adapt. Instead of “hear[ing] mice in the walls,” “now rockets teach him to sit, immobile and sick” (“In a Different Country”).

The war is uninvited, the poet says: “no one [has] made its bed, or set the table.” The poem goes on to ponder how to “wash blood drops / off the white linen” tablecloth (“War. Day 1”). In the midst of sirens, with unsurprising Ukrainian hospitality, the speaker offers the reader tea (“War Day 3”) and suggests they read “Kafka and Kierkegaard, by name” (“Russian Invader, Who’s Forgotten All Chivalry”). Daily life goes on; “war catches a man with a string shopping bag / [. . .] on his way back from the store,” the “bottle of milk and a loaf of bread” (“The Worst is When War Catches a Man”) insufficient for the uninvited guest of the first poem. And a hundred days later (“War. Day 102”), the host asks,

you don’t mind the mess, do you?

we had a rocket fly into the kitchen yesterday.

There are flowers here; cue Wordsworth’s daffodils for a background screen. “War. Day 4” begins: “On the eve of the war I bought rhododendrons.” Planting them, though is disrupted by the sounds of conflict: “an air raid siren is buzzing, the air defense, pounding.” But the speaker in the poem is undeterred: “I live here. It’s here that I plant flowers.” Likewise, the remains of the garden are explored in “Where, She Asks, Are My Irises.” In this poem the flowers have been “denazified” for

preparing an attack,

planning to join the eu and nato,

stockpiling biological bees.

Khersonska identifies a few of the reasons given by Putin for initiating the war against Ukraine, but points out the logical fallacy of the argument. Just as the irises made no threats to the sovereignty of Russia, so the people of Ukraine.

The house, or rather “something tall” is “two-thirds left standing, a heap of shards, a heap of my living pain.” War is seen through the lens of home life. “War is a pile of dust” to be cleaned up as are “sorrow in your shack, / death at your gate, scrap metal in your yard” (War. Day 6). Roofs have “leaks caused by April showers and H.A.I.L. rockets” (“Leave Me Alone, I’m Crying”). And how do we “fortify our windows / so that they don’t explode / into tiny parts and shards” (“War Day 9”) that cannot be put together again? There are bans, the poet says, on “destroying homes and scaring animals to death,” but, unfortunately, “Those bans do not apply in countries / Meant to be taken over” (How Nice to Take a Walk in a Warless World”).

And the children cannot be overlooked –

“Leave Me Alone, I’m Crying”

A little refugee girl from Donetsk: I’ll build a house for the cat,

if you have a home, you don’t get sick and you don’t sneeze.

[. . . . . . . . . . . .]

But rain is hard to explain to the cat

Later, the poet makes the comparison:

in another country a dad carries a daughter in his arms

“In a Different Country”

in my country he carries a weapon

to protect her from the enemy

In “There Once Was a Little Girl,”

it would have been better [. . .]

had she been born farther away –

[. . .] from

the country of cannibals

so that it wouldn’t bite off a chunk

of warm human flesh

skewered on a Sarmat missile.

Nothing in this daily life suggests normalcy to the rest of the world. And the children are affected most of all.

In “War. Day 10,” the barbarity of the war is defended against with books. Here, books filling windows protect “against missiles, against shrapnel, / against glass,” and suggest a literal defense as well as a philosophical one. The truth of books can stop the lies of propaganda, if piled sufficiently high. The poem suggests the title of the present book might be The Recent History of the Middle Ages. In contrast, a year prior, a neighbor “white-washed her house, planted irises, wore neat dresses” (“People Are Tired”). The implied question of the entire collection is, Will those days ever return?

Through the combined efforts of four translators – Olga Livshin, Andrew Janco, Maya Chhabra, and Lev Fridman – Khersonska’s house of words, dismantled as it is, can be understood, its pieces terrible, marvelous, and quietly urgent.

Stan Galloway writes from the hills of West Virginia. He is the founder and host of Pier-Glass Poetry. He is the author/editor of 9 collections, including Endlessly Rocking (Unbound Content, 2019).

Add your first comment to this post