by Nicole Yurcaba

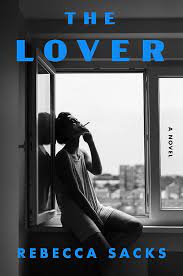

There’s something jarring, and even highly unnerving, about reading a novel in which the events unfold similarly to how a series of events is occurring in real life. The lines between reality and fiction blur, and a reader may find themselves asking, “Didn’t I just read about this on CNN today?” This may very well be the experience of anyone daring to pick up Rebecca “Bee” Sacks’s novel The Lover at this time as the Israel-Hamas war rages in Gaza. The Lover is the story of Allison, a thoughtful academic studying in Tel Aviv who falls in love with the much younger Eyal, an IDF soldier called to duty for a potential invasion of Gaza. Against the backdrop of Allie and Eyal’s love story, Allie encounters the region’s identity and postcolonial politics, and when Eyal returns from the invasion, Allie finds herself so profoundly changed, she questions her future in Israel.

Allie and Eyal’s love story, of course, is paramount to the novel. It is, as readers learn, the main reason Allie decides to apply for a grant to continue her studies in Israel despite her family’s subtle objection. However, for Allie, her decision is also a matter of self-preservation and self-discovery. In Israel, Allie feels complete, and she has found a place she belongs, despite the fact that she is, as she describes herself, “a wrong-half Jew,” since her Jewish identity comes from her father, not her mother. Nonetheless, another complication arises for Allie in Israel — her friendship with Aisha, a Palestinian student attending the same university as Allie.

As Allie’s friendship with Aisha develops, Allie hides many facets of her own life from Aisha. For example, she does not tell Aisha that she is half Jewish, nor does Allie reveal that she can fluently speak Hebrew. The biggest secret is an obvious fact: Allie is in a relationship with an IDF soldier. When Allie goes home with Aisha and hears the Palestinian perspective from Aisha’s grandmother, Aisha pretends to not understand Hebrew, and she learns about the massacres conducted by Israeli forces in the settlement areas. For awhile, Allie is able to disguise her identity, as well as her socio-political alignments, because of a unique philosophical camouflage — the pro-Palestinian talking points she learned from her sister, Erica.

Erica is Allie’s direct antithesis, and their conflicting opinions about Israel and Palestine fuel their volatile relationship. Their relationship, too, is significantly symbolic, serving as a small representation of larger divisions which not only widen existing Israel-Palestine chasms between family members, but also friends, neighbors, and entire countries. Erica, quite frankly, is an easily dislikeable character. Sacks does an incredible job of making Erica dislikeable, thanks to the way Sacks crafts Erica’s dialogue. Erica is superficial. Compared to Allie, Erica seems like a puppet who merely mimics the talking points fed to Erica by her partner, Cee. Unlike Aisha, who actually exists within and functions in the realm of Israeli violence towards Palestinians, Erica seems to adopt her views simply to rebel against her family and please Cee. Readers can also infer that Erica deliberately takes the opposing viewpoint to Allie’s not as means of true, personal belief, but as a deliberate attempt to belittle and degrade Allie. Erica, at one point, goes so far as calling Allie a “fascist” because of Allie’s seemingly pro-Zionist social media posts. Thus, in scenes like these, the novel opens a larger conversation about the perceptions of fascism, nationalism, and cultural and identity politics between Palestinians and Israelis, and even Americans and Canadians, who have a vested interest in either side’s cause.

Eyal, surprisingly, as an IDF soldier also has an experience with a Palestinian which seems to change his own opinions about the ever-raging conflicts between Israelis and Palestinians. Perhaps more so than Allie, Eyal is the novel’s most sensitive character. During the novel’s invasion of Gaza, Eyal watches an Arab man through his rifle scope. The Arab man picks through a building’s wreckage, and as Eyal carefully observes the man, he watches as the man searches for photographs. In this moment, Eyal sees the man as neither Arab, Palestinian, or an enemy. Instead, Eyal sees the man as a fellow human being, whose entire existence has been bombed. What comes next is what breaks Eyal, and its Sacks’s minimalist writing which captures Eyal’s sudden moral conflict:

Eyal isn’t the only one who shoots. You can’t say for sure, he can’t say

for sure, whose shot it was. He doesn’t know. It would be impossible

to know. He can’t know. But when the Arab is hit, he doesn’t make a sound.

He falls without a sound like the coming of night.

The unraveling of Allie and Eyal’s love story, nonetheless, might perplex Western readers unfamiliar with the cultural and social nuances involved in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. At first, a relational breakdown occurs between Allie and Aisha when Aisha sees one of Allie’s social media posts which defends the violent actions of Israeli police forces against a Palestinian boy. Aisha describes the boy’s massacre as an “execution,” and when Allie poses the question “‘What’s so bad about being a Zionist anyway?’” to Aisha, Aisha responds by pointing out to Allie that Allie had visited Aisha’s home, that her grandmother had repeated her trauma for Allie. Similarly, when Eyal learns that Allie went to Aisha’s home, he repeats “You went into their home,” and he claims that he no longer knows who Allie is as a person, because Allie essentially lied to Aisha’s family, and because of her lying, Eyal views Allie as a stranger. In these moments, Allie serves a larger purpose in Sacks’s novel. She is no longer the young academic attempting to understand her own Jewishness and identity, and she is no longer the Canadian slowly transforming into an Israeli and subtly making Israel her home. She is symbolic of Western, particularly American, views which favor Israel over Palestine, and she also represents any number of Westerners who still fail to understand the Middle East.

Despite its gorgeous, minimalist prose, The Lover is an emotionally and politically intense novel. Like Omer Bartov’s The Butterfly and The Axe, it asks readers to find humanity where many feel it does not exist or cannot be found. It is a novel that, for decades to come, both academics and the general reading public will study and talk about. And, for as long as Israel and Palestine remain in conflict, it is a novel that will remain necessarily relevant.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post