by Nicole Yurcaba

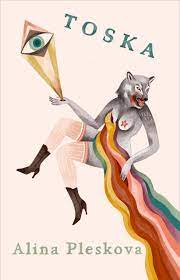

The word toska is a Russian word which roughly translates as “sadness” or “melancholia.” In Alina Pleskova’s debut poetry collection Toska, the speaker’s sadness culminates with dissonance and alienation. The collection carefully explores the loneliness inherent in the immigrant experience in the United States, especially as the US and its policies run towards a more isolationist, capitalist, and bigoted future. The book, too, also celebrates sexual liberation and the revelations accompanying the self-acceptance which so often blossoms when one finds the spaces in which that liberation can occur.

Toska is, essentially, an examination of the places which influence, shape, and transform an individual. It is only appropriate then that the collection harbors a poem titled “Place.” In this poem, the speaker returns to an initial place which readers can infer to be Moscow, Russia. The poem waxes nostalgic as the speaker recalls the place where “my mama went on clandestine blue jeans / missions.” It recalls “the first McDonald’s workers in Moscow” and how they were “trained to smile.” However, the speaker also poses an intriguing question: “What do I get to claim, or blame when convenient?” The speaker’s question posits the disengagement with their homeland one may experience upon immigrating to a new country. This sense of disengagement, however, is a permanent feature throughout Toska, and the final line of “Place” perfectly captures that sense: “You often seem somewhere else, said someone in my bed. As if to explain.” The poem “Hard People” is another poem essential to capturing the speaker’s disconnect and engagement.

The structure of “Hard People”–six left-aligned, blocked, prosaic stanzas–will initially capture readers’ attention. The structure, however, is crucial to the poem’s subject matter. As the poem unfolds, readers encounter the line “Someone on a forum asks, ‘Why are Russians such “hard” people?’” The speaker alludes to the traumas, such as the training “for generations that nothing is yours,” which contributes to outsiders’ perceptions about the Russian people’s hardness. Generational and familial disconnect is also paramount in the poem, particularly in the context of the speaker’s dedushka (grandfather), “a self-taught / master tailor” who “refused to work for the Bolshoi unless he could hire other Jews.” Interestingly enough, the speaker draws on common Slavic folk practices like “knocking on wood” and spitting “over the left shoulder, the devil’s side.” The most noticeable disconnect occurs when the speaker remembers “they tried getting me to write in Cyrillic with my right hand, / but it didn’t take.” The phrase “but it didn’t take” reinforces the speaker’s sense of disconnect and disengagement.

“I Forget What I Returned For” is another standout poem in Toska. Disconnect takes on a different form in it–the severing of a personal connection. The poem incorporates tongue-in-cheek phrasings like “airport vegetable aura.” The speaker’s sense of longing culminates in the lines “I keep idly smearing / an orange-ginger lip balm / you left in an old winter coat–.” Just as in “Hard People,” small rituals hold significant meaning. The speaker’s act of smearing the lip balm is a ritual the speaker employs in order to re-engage not only with the past but also with the mysterious “you.” The poem’s final stanza perfectly captures the speaker’s longing:

how objects, like nicknames,

stick around long after their sources

how people don’t vanish

when you stop loving them.

Toska is an emotionally, even socially, complex collection. It is existential and weary, but the speaker’s desire for life, for interconnectedness, and for others temper that weariness. Its speaker approaches the world with a wry, dry sense of humor. At the same time, the speaker’s observations and revelations are a call to find or create the spaces each individual so desperately needs.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post