by Zosia Paul

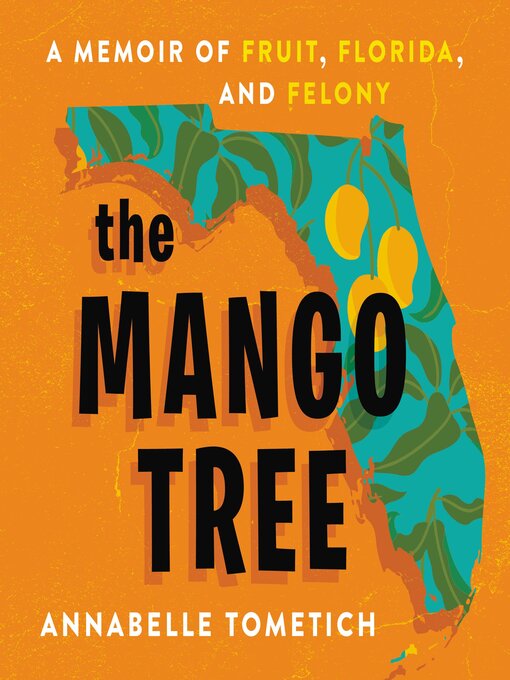

After a fascinating opening that features food writer Annabelle Tometich’s mother arrested for shooting out a man’s window because he took a mango from her tree, Tometich rewinds and shares a complex portrait of her mother and their relationship. Annabelle Tometich grew up in Fort Myers, Florida with her younger sister and brother, mom, and dad. Her mom, who was the oldest of seven, is Filipina and immigrated from Manila when she was young, on a nursing path to citizenship. Most of the descriptions of her mother in the early parts of the book capture her hardworking nature, with observations like, “Mom renounced most of her wants before she could get to know them.”

Tometich also reveals the racism her mother experienced from her white mother-in-law while attempting to take care of her while she’s sick, accompanied by the lack of support from her white husband. Tometich’s grandmother wishes her son had married someone else and regularly makes it known. Her grandmother spews hateful remarks, putting her dad on a pedestal while berating her mom to no end. Even when she had insisted on moving her grandma in with them instead of into a nursing home like her dad had suggested. She noticed how her dad’s life came easier to him, how he was inattentive and didn’t seem to care about his family. As a little girl he would forget to feed her, leading to major burns from the stove when she tried to cook for herself. Her sister once found herself in a similar situation, swallowing a bottle of Tylenol trying to find something to eat as her dad slept. Yet, Tometich, who is mixed-race, confesses she didn’t, “…want to be tough like mom. I want to be fragile like Dad with his white skin that always needs to be protected.”

Not only does the mother have to do most things herself, Tometich also reveals that the family experienced a significant amount of loss. She observes, “Death seems to be following us, clinging to us like mold.” The family attends many funerals, with the death of her grandmother who lived some of her final days in their house, her Tito, who committed suicide while staying with them, and most significantly, however, at the age of nine, her dad died. This is where we get some of Tometich’s strongest writing as she reflects on the abnormal manner of his death. Despite being so young, her mom did not hold back sharing the details with her children. After the two had been in a fight, he had painted the inside of a plastic bag with Wite-Out and put it over his head, suffocating. The family still is unsure if he was just trying to get high, or if it was a suicide attempt.

Tometich recalls how her mom taught her Wite-Out is for mistakes, and found cruel irony in this because her dad was inattentive, unhelpful, and often yelling. While she is devastated to have lost him, deep down she is also scared to have lost her living connection to whiteness, what she considered to be proof that she was somebody. She resented being left alone with her quirky mom who she sometimes told the other kids on the school bus was the gardener to avoid claiming her. Still, in this devastating moment, Tometich empathetically recollects that her mom did what she did best: take care of everyone. “Days or maybe minutes later, our four cried become three. Mom kneels then stands. She brushes herself off and pulls each of us up.”

With a childhood full of so much darkness, the happy moments stand out. One of the only highlight Tometich includes is her mom’s mango obsession. At first, they just went to pick mangoes at orchards, coming home with boxes upon boxes of them. This progressed into her mom nursing two mango seedlings into adulthood in her own lawn. This had always been her mom’s dream: to have a yard full of fruit trees. Every time the tree fruited, the family picked the mangoes and ate them year-round. It was a rare moment of calmness amongst the storm, creating a temporary reprieve from the toxicity her mom poured into the household. “The thunderstorm fights of our parents start to fade from memory. They are replaced, at first, by bag after bag of mangoes, by smile after smile. In fall, the trees stop fruiting and the fights resume.” The mango trees and her mom’s constant care of them serve as a reminder of her mother’s complexity; her sacrifices and dedication and yet at the same time, her tendency for obsession and control.

When Tometich is finally old enough to go to college, she eagerly jumps at the opportunity to escape her household. Ever since she was a kid, she had promised her mom she would help out more around the house in exchange to move the family back to the Philippines, where her mom knew she could get help from relatives. Tometich essentially took on the responsibilities of a homemaker and mother to her two younger siblings, a role she was eager to shed in college. As she became happier and happier at school, making lifelong friends and starting a relationship with her future husband, her mom struggled with being alone. She started to become unhinged, hoarding her house, ignoring her youngest child who at this point was the only one left, and buying a BB gun to kill squirrels that try to eat her mangos. “As Mom’s house has devolved, I feel like I have evolved.”

Eventually, Tometich settled down in Fort Myers to start a family, her house even has its own mango tree. She finds work as a food reviewer, writing under a fake French-sounding pseudonym before finally shedding that and embracing her full Fillipina identity to the world. This is a significant moment in Tometich’s path of finding acceptance in herself, and she writes about it with beautiful insight. One day in her adulthood as she oversees her new family, she receives a call from the county jail, her mom has been arrested for shooting out someone’s window. Years of devolution of mental and physical health had finally culminated into this one act. Through the process of her mom’s trial, Tometich realizes that, “… the court is treating Mom just as harshly and unforgivingly as I have.” She realizes that her hyperfocus on her mother’s shortcomings allowed her to overlook all that she had given her: a life in America, and a person to always fall back on and be there for her in her times of need, like the birth of her first baby. As she tries to wrap her head around the event, she can sympathize and almost understand her mother’s behavior because, “Mom’s children have left her. Her fruit trees have not.”

The one-of-a-kind perspective and experiences of Tometich, combined with her skillful and beguiling writing, make The Mango Tree a powerful story; providing full circle life lessons on the complexity of family, self-acceptance and discovery, and healing.

Zosia Paul is a senior at the University of Tampa, majoring in political science and minoring in writing. She works as a research assistant for on-campus projects and holds executive board positions in University political clubs.

Add your first comment to this post