by Nicole Yurcaba

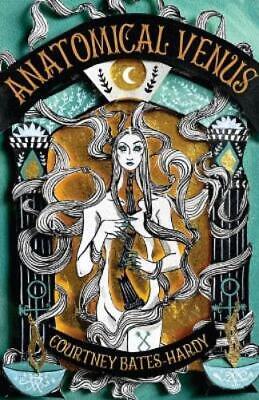

Courtney Bates-Hardy’s Anatomical Venus takes readers on a journey through chronic pain, inherited disease, and the tumults of living in an ableist world. Rife with fantastical female monsters and fascinating anatomical figures, these are intellectually and emotionally sharp poems. Anatomical Venus are gorgeous contributions to a cabinet of curiosities where queer love, the magic of self-awareness, and grief and inquiry reside on full and unabashed display.

Part of Anatomical Venus’s mystique is that Bates-Hardy effectively reimagines the great works of white male poems like Wallace Stevens. In fact, it is an unabashed reimagining—titled Eight Ways of Looking at a Car Accident”— of “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” that opens the collection. Balancing the fine lines between prose and poetry, “Eight Ways of Looking at a Car Accident” bears witness to the moments and liminal spaces where trauma alters one’s life. The speaker balances stark statistics—“one in three rollovers result in death”—and personal speculation—“I wonder how it looked from the outside.” The poem’s structure—eight prosaic stanzas that can also be read like an essay—parallels the speaker’s tragic experiences as well as their acceptance of their survival. Small details—such as the speaker’s observance of “course catalogue that had been in the back of my car for months” and “was lying open on the smooth snowbank”—comprise the poem. This initial attention to detail, however, establishes the speaker’s sense of acute self-awareness, which is an integral force in each and every one of the collection’s poems.

Anatomical Venus also offers readers a reimagining of pop culture icons like The Bride of Frankenstein, whose image was made famous by British actress Elsa Lanchester. Bates-Hardy’s portrayal of The Bride is psychological and contemplates The Bride in juxtaposition to The Monster. As a “reflection of the monster’s / desire,” The Bride “does not exist.” The Bride is not a mirror of The Monster, made in a similar fashion so that The Monster can have a partner. Instead, despite The Monster’s dominance, The Bride possesses her own individualism and her own agency: “Her eyes see beyond his expectations: / she cannot quench his loneliness. // Her pale body reflects the moon.” The speaker’s portrayal of The Bride’s body as an object which “reflects the moon” gives the poem a celestial, otherworldly feel. However, it also reminds readers that The Bride possesses a beauty entirely her own—one that mere humans may not be able to understand or accept.

In many ways, Anatomical Venus is a manifesto calling for a societal reconsideration of beauty and acceptance. “On Living with Chronic Pain” is one of the many poems advocating for such change. The speaker has a minor, yet emotionally significant, moment of self-acceptance when they acknowledge that the nerves in their neck “will never be what they were.” The speaker shares that some days they “live with some pain” while on others they are “all pain / flames spreading from neck to shoulder.” In the poem’s penultimate stanza, however, the speaker’s self-acceptance truly, and brilliantly, culminates:

I am a torch in the dark, burning alone,

but the more I look, I see pinpricks

of light in the distance.

These lines embody a spirit of survival and survivorship, and while they take ownership of the individual chronic pain experience, they also remind readers that chronic pain and chronic illness experiences are also a collective experience for those who receive such a diagnosis.

Anatomical Venus is necessary and immediate, especially as societies and communities reexamine accessibility and strive for equity for those who are chronically ill and/or disabled. These verses examine the various ways an individual holds pain—physically, emotionally, mentally—but deny it its claim on their entire being.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post