by Nicole Yurcaba

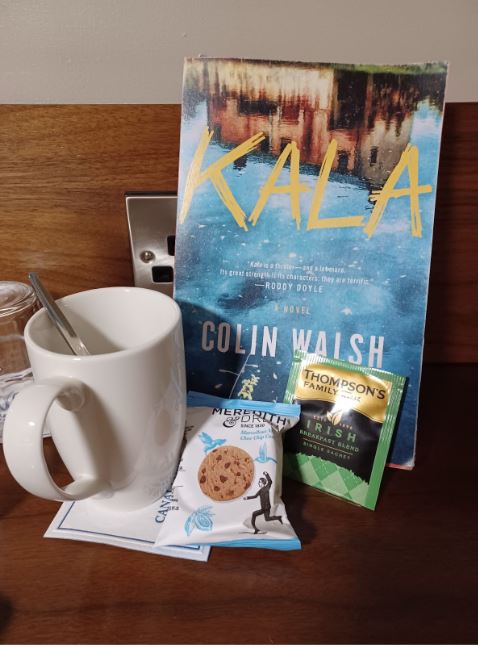

The Washington Post describes Colin Walsh’s Kala as “more than your typical ‘missing girl’ mystery.” For me, the novel is the one with which I began and concluded a recent trip to Northern Ireland, where I attended The John Hewitt International Summer School in Armagh, Northern Ireland. While Kala, which is Walsh’s debut novel, seems to have taken the literary world and shaken it up a bit, about halfway through the novel I found myself wondering “When is this going to end?” It’s a novel filled with vanishings, betrayals, violence, and the darker side of rural Irish life in the early 2000s.

Kala is an intricate novel, told from the perspective of three friends whose adolescent years are tainted by the disappearance of the confident, puzzling, and unique Kala, a young woman whose existence is a complex mixture of abandonment, otherness, and strange circumstances. Kala befriends Helen and Mush, two teenagers navigating their own social and familial awkwardness. Kala also develops a relationship with Joe, a young man whose family’s well-to-do status in the small town of Kinlough allows him a rather privileged life compared to his peers. Fast forward two decades, and readers find themselves in a modern setting, where Helen has become a freelance journalist in Canada, Mush has remained a steady hard-working figure in his mother’s Kinlough cafe, and Joe has risen to the stardom’s heights as a popular musician. The deep wounds each incurred after Kala’s mysterious disappearance reopen when her remains are found in a soon-to-be-developed wooded area in Kinlough. However, the discovery of Kala’s remains not only reopen the past for Joe, Helen, and Mush; the discovery also pushes Kinlough’s rampant corruption and misogyny into an open space for all to see.

Kala’s 400 pages might intimidate some readers, and at times other readers may respond the way I did as I read the novel on a dreary evening in a Newry hotel room– “Can he just get on with it?” However, what redeems Kala from even its most boring parts is how effectively Walsh portrays each character, especially Kala. Rebellious and individualistic, Kala is, by far, the novel’s most memorable and symbolic character. She’s a dark storm, an emotional hurricane of “shea butter, tea tree oil and tobacco” whose “crooked eye is already elsewhere.” She is part of “The Other Place,” as Joe says, which even for her friends is an unattainable place of being, a detached-from-reality realm where only dreamers like Kala can thrive. A tidepool of music and eyeliner, Kala also represents a simpler time for teenagers, when CDs and flip phones rather than social media and smartphones, defined a generation. Thus, her disappearance represents the dramatic end to a special era, specifically for Millennials, who left behind their CD stacks and mixtapes and have spent their young adulthoods exhausted and broke.

Of course, one can’t read Kala and not notice the subtle stabs Walsh makes at Irish existence. Primarily, this occurs through Mush’s character. An intelligent, philosophical, and sensitive young man, Mush is bound by an unspoken duty to take care of and help his mother. As a teenager, Mush felt more comfortable hanging out with Kala and Helen rather than with Joe and some of the other male characters. Mush cannot express his preference, fearing judgment from his mates. Mush stands as the juxtaposition to current Irish male society. According to Professor Brendan Kelly, Irish male happiness rates slightly above overall European male happiness, but certain men “express their masculinity through bodily perfection.” Mush also fulfills another consummate stereotype of Irishmen–the consummate alcoholic. He enjoys his evenings of drinking cans of, as readers can assume, beer while sitting in a booth long after the cafe has closed. In fact, alcohol consumption–not only by Mush–plays a significant role in Kala. Joe is a recovering alcoholic who backslides. Thus, both characters uphold a long established, and dangerous, Irish stereotype. As The EPIC museum asserts, the stereotype stems from British media, which satirized and commented on Irish drinking since the 16th century.

Thus, as readers can see, when one endeavors to look beyond Kala’s murdery-mystery surface, they find a novel riddled with socio-economic commentary. However, it might just take readers a seven-hour flight to Dublin, a night in Newry at the Canal Court Hotel, and a seven-and-a-half hour flight from Dublin to Washington, DC to find them.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post