by Stan Galloway

Katie Farris proclaims in the opening poem of Standing in the Forest of Being Alive (Alice James Books, 2023, 57 pages) that she writes “[t]o train [her]self in the midst of a burning world / to offer poems of love to a burning world.” To do this, the poet skirts the pity and the blame of her ordeal with cancer and, borrowing from Emily Dickinson, tells it slant, finding oblique beauty and hope. “This cancer patient has ambition,” she writes in “Woman with Amputated Breast Returns for her Injection.” She is, after all, as the title of the collection affirms, “Standing in the Forest of Being Alive.” And that is a state of wonder and meditation. The poems are, like memory, “a prophylactic against loss” (“Against Loss”). While loss is evident in the collection, it is not its center.

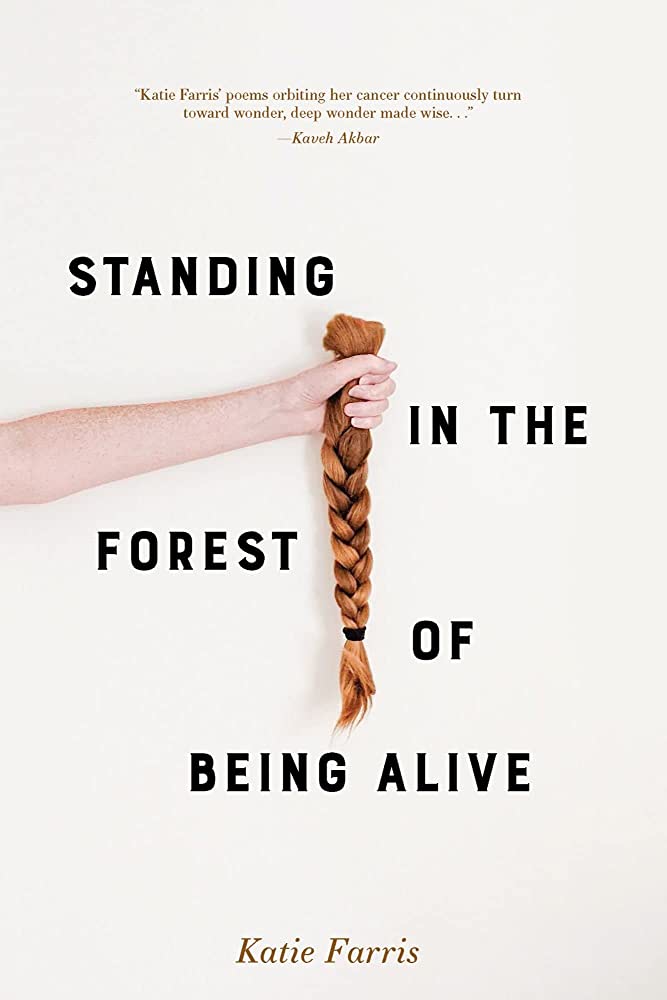

The cover illustration (a photograph by Anne Sullivan) is of a woman’s arm reaching from outside the frame gripping a severed braid of hair. The meaning clarifies in “On the Morning of the Port Surgery,” where Farris writes, “[I] surrender / my braid,” before becoming “Cancer Patient, Stage 3.” The personal and impersonal fight for supremacy, the braid becoming the first loss. She writes later,

In the event

of my death, promise you will find my heavy braid

and bury it.

The braid is not lost, only separated, as if an entity on its own to be found again. This request for braid burial is not a sentimental gesture, but a reasoned strategy: “I will need a rope / to let me down into the earth” (“In the Event of My Death”).

The cover image of the braid recurs in the book as section dividers, except the image has been geometrically rearranged into triangle units reshaped as a diamond, eight triangles refit together as a square standing on its corner. At the end of the collection these triangle-based diamonds form a reconstituted braid, not a repetition of the cover but a fragmentary resurrection in a new form. That image of keeping elements of the old but making something new becomes as powerful as any poem in between.

Like the braid, the breast, where the cancer was discovered, becomes a separate entity. Even before removal, the poet addresses her breast in the third person. In “Emiloma: A Riddle & an Answer,” she asks, “Will you be / my death, breast?” The body is viewed in terms of separate objective parts. The impersonal does not always win, though. Creating the personal in the impersonal world, she names her cancer “cactus,” because, she writes:

you make

“Tell It Slant”

a desert of all

of me”

Naming the carcinoma is the first step of objectification and an extension of identity, as accorded the braid and the breast. The body is made of identifiable constructs that work together or fight against each other. The breast, for example, is both enemy and ally. Her humanness has not dried up in the desert that cancer has brought. In evidence, she still desires to be loved.

In such poems as “The Man You Are the Boy You Are,” “If Marriage,” “Contrition,” and “In the Shadow of This Valley,” the husband is addressed as lover. In “To the Pathologist Reading My Breast, Palimpsest,” she admits her breast has received not only kisses but “a couple (playful) too-hard twists / and late-night drunken dare-you strips.” And in “The Wheel,” post-surgery, she affirms to him, “I like my body / when it’s with your body.” Love endures, even when the body is altered.

In “A Row of Rows,” the speaker and listener (poet and husband) argue about

“whether

it’s okay to throw apple

cores in the street.”

The speaker objects to this. Later, in “Eros Haiku,” the apple core reappears as a symbol of the speaker in a form that suggests both desiccation and desire. In both references the apple core is broken into two parts by a line break, reinforcing the brokenness brought on by cancer.

One element that the cancer has not dried up is the erotic impulse. In “An Unexpected Turn of Events Midway through Chemotherapy,” she asks for “some sex please.” The sex here is literal and poetic. She recognizes that the body does not meet the visual or even tactile standards it once did. She says she is “not too picky” because of this, and the sex can be “rhymed / Or metrical.” She suggests it need not even be penetrative, “so long as [she and her husband are] naked.” The poem speaks to the changes of the body and the effects on self-image. The sex in this poem is a request for affirmation. It is as much for the mind, which has not changed, as it is for the body, which has. Nakedness is essential. It is the willingness to face life, and each other, with nothing, not even the scars, hidden. It is stark honesty about what these lovers are going through. And affirmation and honest companionship become the erotic byproducts of her request.

The sexual element elides into comfortable familiarity as well. The breast, with its “soft everted nipple” has been a source of comfort to the poet, a place, she says, for “my own homely grip / as I skidded into sleep” (“To the Pathologist Reading My Breast, Palimpsest”). The patterns of life are disrupted, their loss regretted, their memory, post-surgery, nostalgic.

Inevitable grief after the breast is removed is defined as:

“love

“Woman with Amputated Breast at her Mother-in-Law’s Grave”

which has teeth, and

eats”

And in the process of grief, “One must train oneself to find, in the midst of hell, / what isn’t hell” (“The Wheel”). That is what this collection reaches: non-hell in the midst of hell, what isn’t burning in a burning world.

Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and Robert Frost make appearances to provide encouragement along the way. The inclusion of other poets makes the collection more clearly a conversation with tradition as well as providing a sense of transcendence. The idea of the immortality of words becomes a subtle undercurrent in the book. Jericho Brown writes that these poems “question and praise the body even as it deteriorates” (back cover). Farris’s book takes a positive look at fireproofing life, even while the world burns.

Stan Galloway writes from the hills of West Virginia. He is the founder and host of Pier-Glass Poetry. He is the author/editor of 9 collections, including Endlessly Rocking (Unbound Content, 2019).

Add your first comment to this post