by Sadaf Pauls

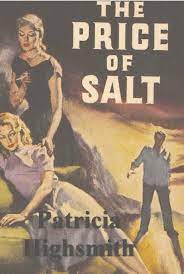

Recently I was spending a few weeks in a warm Mediterranean country, and amidst the stunning landscapes and sunny days, I was going through a painful process of self-identification. The contrast with my inner world was stark but I was grateful to have the time to reflect on how new people and new places allow me to reinvent my personal narrative because they simply do not put me in a box. By the end of my trip, I had met The Price of Salt, and now I know that it was meant to be there for me and be that new “person” with whom I had no past, who had no expectations of what I am supposed to be. Thus, writing a review for Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt or Carol was an intimate reiteration of observing a narrative that unexpectedly became so significant during an uncertain period in my own life.

The Price of Salt is the story of Therese, a future stage designer who is just starting out in life. One day Carol walks into the department store, where Therese works, looking for a doll for her young daughter. Their attraction is immediate; Carol, in the midst of a bitter divorce, finds herself mesmerised by this mysterious, quiet girl. The two women’s gritty love story unfolds on a road trip across the United States. But when Carol’s husband grows suspicious, she must end her trip with Therese and return to New York, where she is engaged in a battle for the custody of her child. Carol and Therese’s challenges arise from their emotions conflicting with societal norms, making their situation unique. Caught in the delicate balance between choosing her daughter and the raw, yet overpowering relationship with Therese, one navigates the familiar landscape of 1950s queer narratives– will Carol choose her child, return to her husband, or lose herself in the process?

While the novel defies the conventions of its time by portraying a love story between two women, its beauty lies in rendering a profound sense of recognition and identity to many women, a sentiment that endures today. The narrative unfolds through Therese’s lens. She illustrates the humiliation and ecstasies of first love while discovering her identity and desires. The plot is raw, yet intimate and relatable, and as the relic of Therese’s relationship with Carol is revealed, we sense a different dynamic than a “conventional” love story; Therese’s internal struggles do not just arise from societal disapproval of her love for Carol but from witnessing her new desires evolve without any influence from her past experiences. The Europe trip with Richard now feels askew, conflicting with her longing for Carol: “She did not have to ask herself if it was right; no one had to tell her.”

The novel is tinged with an air of sophistication and introversion, which is a catalyst for both character’s growth. Therese’s gradual discovery of her identity lends itself to her creative thriving. In the early part of the book, she is unhappy in her relationship with Richard and hates her job, only conforming to what she has to do. But at the conclusion —a grown-up woman —she is completely aware of the steps to manifest what she wishes. Highsmith adeptly weaves the happiness that comes with freedom and creativity in her novel and shows that Therese and Carol’s relationship is beyond a depiction of a queer relationship as a means to break societal norms. As Therese muses: “How was it possible to be afraid and in love… The two things did not go together. How was it possible to be afraid, when the two of them grew stronger together every day? And every night. Every night was different, and every morning. Together they possessed a miracle”.

I savored The Price of Salt. Reading it coincided with uncertainties of revisiting my ruins, and while the emotional and personal lives of Therese and Carol spatialized in hotel rooms and on roads, I was navigating the labyrinth of my own identity. Therese’s self-discovery stirred up emotions in me that vacillated between liberation and fear. But I knew that I held in my hands a novel that was not just a piece of historical fiction but a gentle reminder that struggles of finding oneself transcend time and societal expectations. Ruin could sometimes mean a new life. And perhaps like Therese, after a brief flirtation with our worn-out identity, we would realize that our ruins lay out the possibilities of different prospects. As Therese finally testifies: “It would be Carol, in a thousand cities, a thousand houses…in heaven and in hell…”.

Based in Hamburg Germany, Sadaf Pauls is a polyglot writer and language enthusiast. Graduating in 2024 with a BA in Creative Writing from SNHU, her creative journey includes writing poetry, creating content for a Berlin sustainable fashion blogzine, and freelancing as a bilingual interpreter for trauma therapy. For now, she is exploring her voice in poetry and finding community through words.

Add your first comment to this post