by Nicole Yurcaba

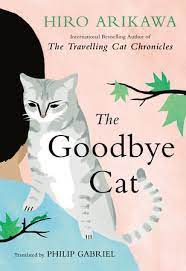

On 5 July 2023, I not only began a new faculty position at a West Virginia community college. I also arrived home and proceeded to the mailbox, where I heard a peculiar noise. At first, I thought some random bird squawked incessantly, making a high-pitched noise. I looked above me, beside me, and around me to spot the bird. However, what I discovered was not at all a bird. It was a calico kitten tucked into a rather large, tangled brush pile a few yards behind the mailbox. It had been an arduous drive home: the car following behind me at a light was abruptly rear-ended; being unfamiliar with my new commute, I made the wrong exit and spent 20 minutes re-routing myself. The last thing I needed on this hot, sticky July afternoon was a kitten. I am already a cat-mom to two very beautiful black cats. Taking in a third wasn’t a feasible option. Nonetheless, a few minutes later, the kitten–which, that evening, I christened “Kate”–toddled about my front porch, meowing, meowing, meowing no matter how much food and water I gave her. Needless to say, the arrival of Hiro Arikawa’s lovely and warm short story collection The Goodbye Cat a few days later to my mailbox was much less dramatic than Kate’s entry into my life. The Goodbye Cat, translated by Philip Gabriel, is the follow–up to Arikawa’s rather successful novel The Traveling Cat Chronicles, and it’s not a short story collection which readers easily surrender when bedtime beckons.

I know that I didn’t.

The Goodbye Cat, much like the lives of any cat owner, is filled with an array of memorable cats. Readers meet Spin, the abandoned kitten discovered in a mandarin orange box by a struggling manga artist who helps the artist embrace fatherhood. They purr over Hachi, the loveable “laid back” cat whose life upends when his young owner must surrender Hachi to a new family when the owner’s parents are killed tragically. Nana, the traveling cat, reminds readers that sometimes it is the unlikely, unusual relationships which impact readers the most. The Goodbye Cat balances just the right amount of sadness, happiness, and every emotion in between to keep readers turning its pages. Nonetheless, it also does something else. Not only does it explore human-to-human relationships and human-to-animal bonds, it presents life’s segue into death, for animals and humans alike, as a mere change of seasons and it provokes readers to think about how what one does in between is what matters most.

Kindness, and the ways one shows it and passes it forward, is a prominent theme in the collection. Initially, readers might respond to each story’s incorporation of a human saving a cat, or cats, in need. Nonetheless, Arikawa’s gorgeous, minimalist approach to prose tricks readers in the best ways. As readers navigate each cat’s story, readers discover that it is the cats, and not necessarily the humans, who perform the act of saving. This is most evident in the story “Bringing Up Baby.” In it, Keisuke Tsukuda is a struggling, socially awkward manga artist who, much to his wife’s chagrin, is unprepared, and unwilling to prepare, for fatherhood. While his wife is away at her parents’ home, delivering her and Keisuke’s baby, Keisuke discovers a kitten abandoned in a dumpster. When his wife returns, she resents Keisuke’s sympathy towards the kitten, which he has named Spin. However, Spin has a few lessons to teach both Keisuke and his wife. Caring for Spin in turn makes Keisuke more responsible, even more attentive to the baby, and this behavioral turnaround impresses Keisuke’s wife. Spin also contributes to Keisuke’s professional rebound: editors take an interest in Keisuke’s manga featuring Spin and the baby. Nonetheless, the story also offers readers a few philosophical anecdotes about what it means to be a creator–something that will resonate with many readers given the ongoing discussions about human creativity and its relationship with artificial intelligence. One of the most striking observations comes from Keisuke’s wife: “Creators were human beings, and human beings instinctively cared how others reacted to what they created. How many people in the world, when ordered to put a lid on that instinct, could actually comply?” Perhaps the same insight applies to kindness and compassion.

“Life is Not Always Kind” is another of The Goodbye Cat’s signature pieces. Its plot mirrors that of The Travelling Cat Chronicles, which may lead readers who explore more of Arikawa’s work to ask “Which came first?” Again, Arikawa’s knack for tapping a philosophical vein that explores human-animal relationships shines. The story features Satoru, a young man who keeps Nana, a cat with whom Satoru often travels. Satoru, for reasons the readers has to work attentively to discover, is faced with finding a new home for Nana. Nana, however, is truly the story’s star. Not only is Nana the primary narrator, Nana is also the wisest character. Nana makes some pretty stark observations about humans, especially in regards to human instincts. For example, as Nana contemplates the boundaries between childhood and adulthood, Nana asserts that it is “kind of vague,” and children “believe in that boundary who announce that this is how adults should behave.” Nana also observes that humans have only one choice, and that is to “flounder around, searching for a vague boundary, certain that they are right.” Nana describes humans as creatures who “only think they know what it means to be an adult.” While the societal consensus might be that adulthood was once something into which one slowly evolved, more and more Millennials and Gen-Zers are challenging adulthood’s conventions and boundaries. In Nana’s case, Nana challenges Satoru to remember that Nana, too, is a living creature affected by his decisions.

I’m unsure what would have happened to Kate had I left her in the brush pile behind the mailbox. Since she arrived in my home, my days have been significantly brighter, even if she does occasionally knock over the to-be-read pile. And that’s what the stories in The Goodbye Cat remind readers–that sometimes it takes a cat to remind us to think beyond ourselves and our needs and to think of and take care of others.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post