by Nicole Yurcaba

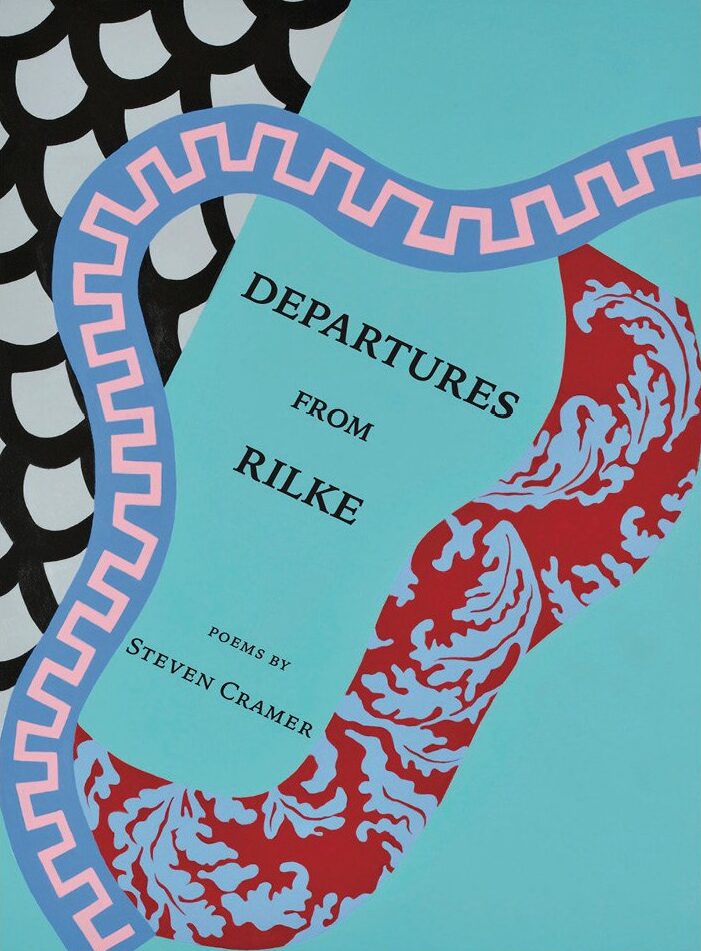

It’s difficult to describe a book like Steven Cramer’s Departures from Rilke, because as one reads it, one feels unsure whether the verses it houses are translations, personal interpretations, or original compositions. Quite frankly, this amalgamation of possibilities is what makes it such a beautiful, philosophical collection. In the afterword, the author provides some clarity for readers: “Provoked by impossibility, then, I’ve tried in these departures to turn limitation into license.” The author then describes the process of “engaging a selection of Rilke’s New Poems in various incarnations,” such as “the original plus English versions” and then “revamping, updating, debating, or upending them.” Cramer’s departures transcend the English language’s boundaries and limitations, and if anything, introduce a new generation of readers to the emotional, structural, and psychological possibilities inherent in Rilke’s poetry.

The collection opens with “Olive Country,” a poem in which the speaker openly questions their faith. The speaker poses questions such as “why do You insist I pray to You?” Hopelessness drips from lines like “You not alone, You I cannot find; // weak in the others, absent in stone, / missing when we are together.” The sense of aloneness and absence grows as the poem’s tone shifts from the personal to the objective and the speaker relies less and less on first-person and second-person pronouns:

The night that came was in everyday night,

like the hundreds that leave us to our dust,

nights that dogs sleep through, and stones,

nights that suffer all night into morning.

The repetition of the word “nights” reinforces the speaker’s allusion to suffering, and it also shapes an inescapable cycle, a sense of churning and grinding, within the stanza from which readers have difficulty breaking.

Cycles—both literal and figurative—are something from which Departures does not shy. Specifically, the collection embraces the death cycle, particularly in poems like “On My Death Bed” and “Morgue.” It is only appropriate that the two follow one another in the book. “On My Death Bed” wrestles a dying individual’s final moments into three stanzas. Words like “leaching” form the slowness sometimes associated with dying. “Morgue” echoes this slowness, especially as the speaker boldly asserts, “Their bodies wait for some intervention.” The speaker likens the intervention to “a ritual—dreamed up too late, of course—.” While emotional distancing between the speaker and the dead is inherent, and necessary, the speaker surprises readers by recognizing the dead’s humanity. The speaker observes, “Their worlds are over, but their names— / why couldn’t we find them in their pockets?” The speaker also acknowledges the importance and necessity of the coroner, who gently cleans the deceased’s bodies. Again, the works make a philosophical shift, acknowledging that death is an unavoidable piece of the cycle.

Nature, too, makes its grand showcase in Departures. “The Duck” is an exceptional piece, one in which the structure creates internal momentum. Repetition again plays a key role in forming the poem’s rhythm. This technique is immediately noticeable in the first stanza: “The work that’s doomed to stay undone— / that type of work walks like a duck walks.” Both “work” and “walk” repeat, working together to create a sonic version of a duck’s waddling, especially one reads the lines aloud. Death makes a conceptual reprise as the speaker acknowledges that death “walks,” “age after age,” like “a duck // toddling to its pond.” The final stanza, however, might leave readers chuckling: “The duck finds all this infinitely boring / and doesn’t swim away so much as glide.” Readers might interpret the duck’s actions as complacency, but the duck’s actions quack louder than one might realize: the duck’s actions are an act of resolute acceptance of the cycles and shifts it cannot change.

Departures from Rilke also does not shy away from difficult socio-economic issues innate in current society. “Immigrant Family” takes a stab at society’s response to immigration and its acceptance of immigrants. The speaker alludes to an unspecified “they” which “look to you like just a clot / of grime your city collects out of nowhere.” One can interpret the “they” as the unwelcoming, nativist societal members who discriminate, rather than welcome, immigrants. These opening lines echo an unsettling occurrence happening globally, but especially noticeable in the United States—an increase in the number of anti-immigration extremist groups. According to Southern Poverty Law Center, these groups support “draconian immigration enforcement” and work to “stall legislative relief for immigrants and their families and to spread bigoted messages.” Cramer’s poem captures the emotional and psychological effects, particularly the distrust, which forms when immigrants are rejected rather than accepted by society. The speaker eloquently captures this distrust in the final stanza’s two lines: “…then suddenly a hand thrusts out— / do you take it if you don’t know whose it is?” This question flawlessly captures how the constant discrimination experienced by many immigrants influences an immigrant’s trust relationship with their new country.

Thus, Steven Cramer’s Departures from Rilke distills life and society’s difficult areas into palatable, poetic pieces which readers can savor and contemplate. It is personal yet universal, linguistically delightful, metaphysical yet real. In it, Cramer accomplishes what so few writers ever can.

It is available from Arrowsmith Press.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post