by Nicole Yurcaba

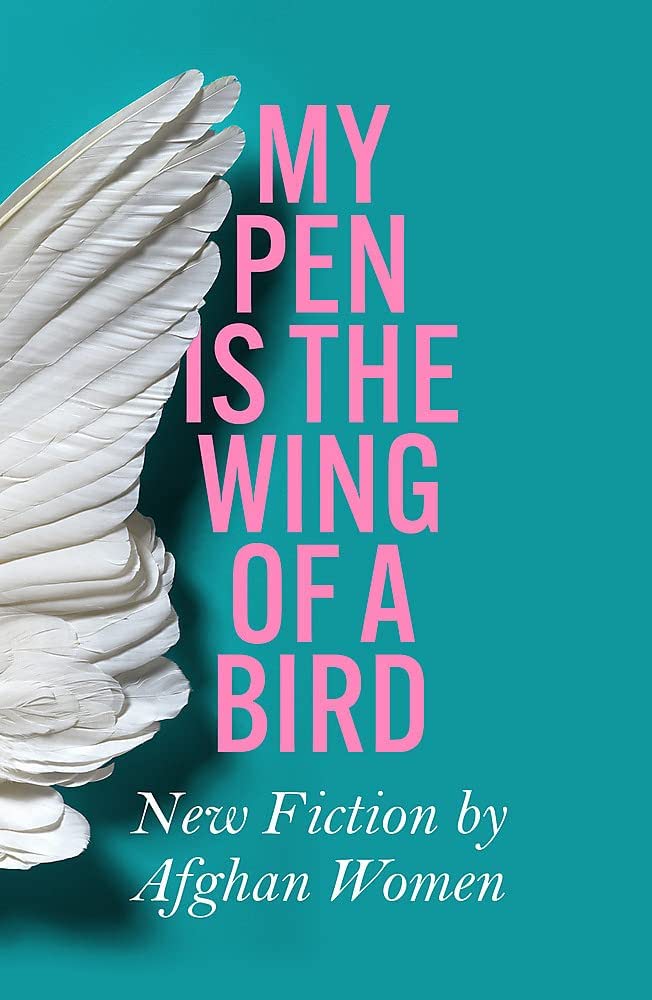

As of January 2023, under the Taliban, life for Afghan women has become even more limited since the ultra-conservative rulers reclaimed power. Secondary schools for girls have been closed. Women have been banned from attending university. They have been stopped from attending parks and gyms and must adhere to strict dress codes. In the worst winter in a decade, at least 124 people have died, and half the population faces hunger, but the Taliban refuses to lift its ban on female aid workers. Day by day, the situation for women in Afghanistan worsens. In the afterword of the anthology of new fiction by Afghan women My Pen is the Wing of a Bird, Untold Narratives founder Lucy Hannah states, “Short stories lend themselves to fractured, pressured environments. It makes sense that a form which contains complexity, beauty, and truth in so few words, on such small canvases, feels easier to produce than something longer.” In the context of the deteriorating everyday reality faced by Afghan women, an anthology such as My Pen is the Wing of a Bird stands as a voice of defiance, and the fiction within the anthology reinforces how artistic and literary expression is one of the ultimate forms of political defiance.

Translated from the Dari and the Pashto, the stories in My Pen is the Wing of a Bird offer hope where so many would not find any. Underlying in the many layers of restriction, oppression, domestic abuse, and even murder is a single, common thread — female resilience. In stories like “A Common Language” that resilience forms through a single act of solidarity when young Naghmah’s female coworkers leave their jobs after their boss, Mr. Soroush, touches Naghmah inappropriately. Even though the narrator and the other young women face various, personal financial crises because of their decision, their faith reassures them, and they enter their future with hope.

A similar theme unfolds in “Ajah,” a story in which Ajah Ayuub, an older woman who had no children, harnesses her determination and saves her village from drowning. As a woman whose family perished when she was young, Ajah “knew what it meant to live with grief and she bore the pain of her loss without a word” as she went about her existence on the border of Uzbekistan in the district of Chimtal. The story’s historical setting is significant: part of it takes place in July 1940, “around the time that the government had announced that every able-bodied man must serve in the army.” At this time, an earthquake strikes the district, and a huge fissure splits the foot of the mountain. Ajah knows the melting snows will cause floods. Despite the jeers and sneers from many of her neighbors, Ajah remains stalwart and motivated to dig a drain and divert the waters. At first, she works alone, but eventually other women join her. The story leaves readers with a simple, yet overwhelming, message about the power of cooperation: “’How difficult is digging a tiny channel when we women come together?’”

Other stories, like “The Red Boots,” remind readers about how a single individual’s bravery has the power to inspire and transform the collective. In this story, a young, unnamed narrator falls in love with a pair of red leather boots. Even though the boots are too small, the narrator convinces her father to buy her the boots. She wears them everywhere, but eventually the boots begin blistering her feet. The narrator recognizes, “I didn’t want to let them go. They would barely last a moment longer, but I loved them as much as when my father had first bought them for me.” As the school year’s beginning celebrations unfold, a classmate notices the narrator’s red boots and calls her out for not wearing the same shoes as everyone else. The narrator determines that, even if it means forfeiting her place in the festivities, she wouldn’t exchange her boots. Nonetheless, the classmate’s intentions backfire, and the narrator becomes the choir’s leader. For some, the story may simply be one about a child determined to hold onto a pair of red boots. For others, nonetheless, a deeper message emerges: for those who hold onto democratic values and believe in conquering oppression, the journey can be lonely, but in the end, the rewards are great.

Recently, a BBC article highlighted the personal stories of three young women whose professions the Taliban disrupted. Such articles remind readers that the stories contain in anthologies like My Pen is the Wing of a Bird may be closer to fact than fiction. Of course, these works are delivered to readers via the intense work of organizations like Untold Narratives and the five translators involved in the project. Thus, the collection is a careful reminder about not only the ever-growing humanitarian crisis Afghan women face in their home country. It also suggests that the role of literary organizations and translators is a universal necessity.

Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба–Nikola Yurtsaba) is a Ukrainian (Hutsul/Lemko) American poet and essayist. Her poems and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, West Trade Review, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Add your first comment to this post